As we observe Hispanic Heritage Month, we recognize the many contributions of Hispanic scientists and researchers who have advanced our understanding of the immune system. Their groundbreaking discoveries in the principles of immunology shaped our knowledge and improved lives globally. This month, we will highlight some of their many accomplishments and the foundational work they performed. Their achievements are a testament to the strength and innovation within the Hispanic community.

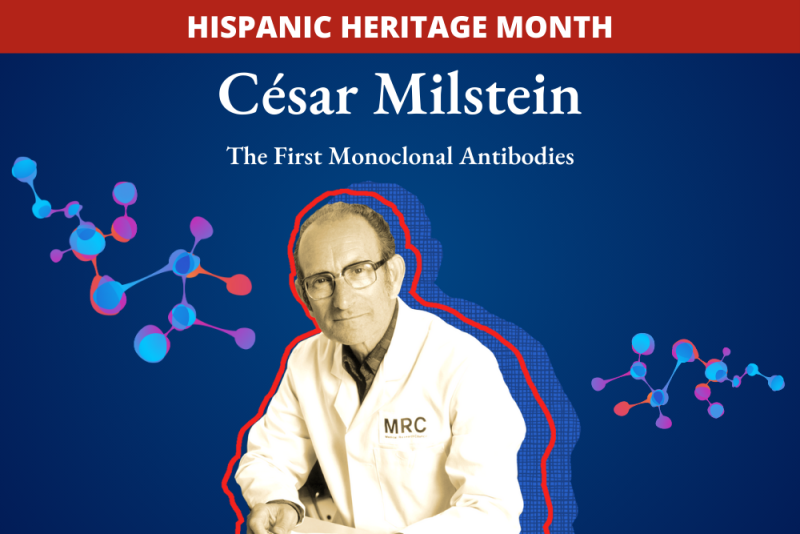

César Milstein (1927-2002), Nobel laureate

When confronted by viruses or bacteria, the human immune response generates a vast diversity of antibodies. This "everything-but-the-kitchen-sink" approach often results in a complex mixture of B cells and immunoglobulins, which, while great for our bodies, complicates research on how antibodies are generated and work. However, in 1975, César Milstein addressed this challenge by developing the first monoclonal antibodies, earning him a pivotal role in modern medicine.

At that time, researchers faced difficulties in creating specific, pure antibodies that effectively targeted specific antigens in pathogens. While mouse spleen B cells showed promise, the antibodies they produced were short-lived and impractical. Milstein, along with his postdoctoral researcher Georges Köhler, ingeniously fused these spleen B cells with immortal myeloma cells, resulting in the production of large quantities of long-lasting, identical (monoclonal) antibodies. Their groundbreaking work led to Milstein sharing the 1984 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Köhler and Niels K. Jerne.

“Science will only fulfill its promises when the benefits are equally shared by the really poor of the world.”

— César Milstein

Since then, Milstein's hybridoma technique has been applied to create a versatile range of antibody hybrids, enabling the development of numerous assays and diagnostics, including pregnancy tests, and as the latest tools in the treatment of cancers and autoimmune diseases.

Much of Milstein’s research focused on understanding antibody structure and the mechanisms behind antibody diversity. His collaboration with Köhler in 1975 on the hybridoma technique marked a significant advancement in monoclonal antibody production, a breakthrough that transformed the landscape of scientific and medical applications. Milstein made numerous key contributions to refining monoclonal antibody technology, particularly in using these antibodies to differentiate between various cell types. In partnership with Claudio Cuello, a fellow Argentinean scientist, he helped establish the use of monoclonal antibodies as probes for investigating pathological pathways in neurological disorders and other diseases. Their work also enhanced the effectiveness of immuno-based diagnostic tests. Furthermore, Milstein recognized the potential for creating valuable ligand-binding reagents through recombinant DNA technology, which spurred advancements in antibody engineering, leading to safer and more effective monoclonal antibodies for therapeutic use.

Born to impoverished immigrant parents in Bahía Blanca, Argentina, Milstein studied at the universities of Buenos Aires and Cambridge, where he earned his PhD. In 1961, he became the head of a new Molecular Biology department at the National Microbiological Institute in Buenos Aires. However, he resigned a year later, frustrated with the political interference in his laboratory that followed the 1962 military coup in Argentina. He then spent the remainder of his career at Cambridge, holding dual Argentine-British citizenship.