Carolyn Coyne, PhD is the George Barth Geller Distinguished Professor of Immunology, Professor of Integrative Immunobiology, Professor of Pathology, Professor of Cell Biology, Member in the Duke Human Vaccine Institute, and Member of the Duke Cancer Institute.

Briefly describe your upbringing, where you are from, where you went to school.

I was born in Flint, Michigan, but moved to Florida when I was quite young so have always viewed Florida as my childhood home. I attended Florida State University as an undergraduate, where I majored in Biochemistry.

What inspired you to pursue a career in science and academia?

I wasn't always drawn to science; in fact, I was a latecomer to the field, with my curiosity starting gradually over time. Initially, my interests lay in neuropsychology, but fate steered me towards mandatory science courses—topics that I had skillfully dodged until then! Surprisingly, it was in my organic chemistry classes that my passion ignited, propelling me to shift my focus to Biochemistry, complemented by minors in psychology and Russian.

I found myself exposed to the world of pharmaceuticals while working as a pharmacy technician throughout most of college. It was here, amidst the shelves of medications, that I began to consider the mechanisms behind their efficacy. Encouragement from seasoned pharmacists planted the seed of considering a PhD program—a notion that gradually took root.

My journey to an academic career was similarly serendipitous, evolving during my post-doctoral training. Recognizing my love of hands-on laboratory work, I consciously veered away from paths that would distance me from the bench. It was this unwavering affinity for bench work that steered me towards academia. For nearly 17 years, I relished every moment spent at the bench until I transitioned away from it just a year or two ago—a chapter of my life that I certainly do not consider closed.

Describe your research interests and the focus of your work?

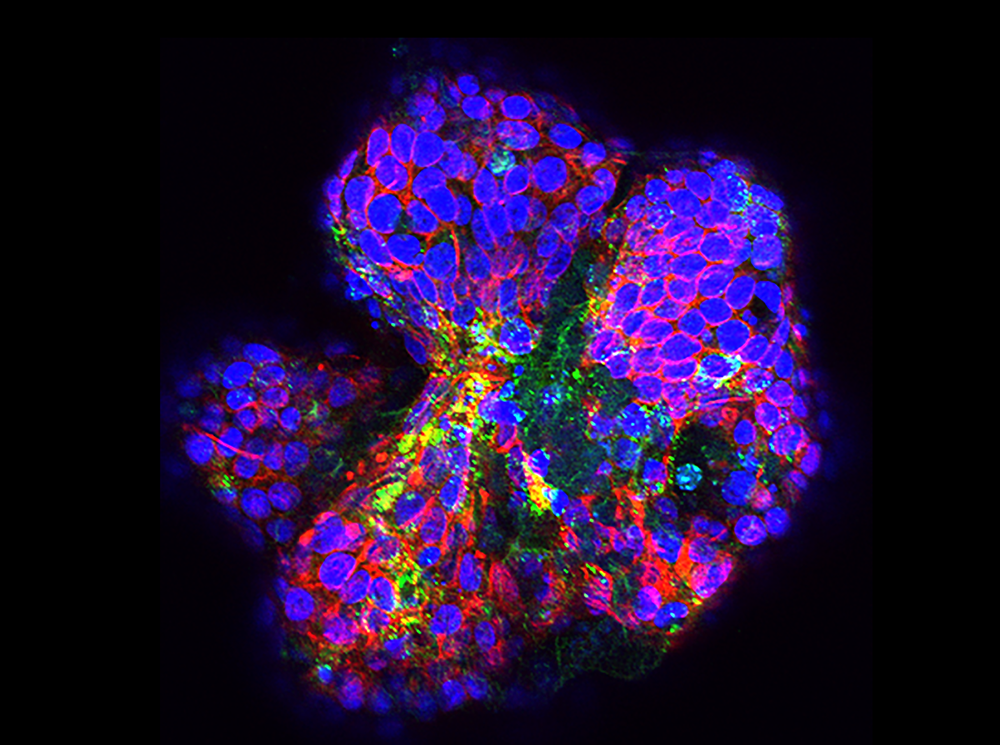

My lab studies the mechanisms by which cellular barriers, such as the gastrointestinal tract and placenta, defend from microbial infections and how microbes that cross these barriers circumvent these barriers.

Can you share any experiences or challenges you've faced as a female scientist in academia?

Throughout my journey in science, the persistent challenge I've encountered as a woman is the unjust labeling of myself and fellow women as "difficult." This classification often compels us to make more compromises than our male counterparts, sometimes to our detriment, and discourages us from advocating for ourselves and our labs as much as we rightfully should. While strides have been made in other aspects of being a woman in STEM over my 17 years as a faculty member, this enduring barrier remains one of the most formidable obstacles for women in academic science that I grapple with consistently.

Any other information (personal or work-related) that you’d like to share?

I started working on the placenta when I was pregnant with my son and became fascinated by what I see as the most remarkable, yet profoundly overlooked, organ in human biology. I credit him, and his placenta, with inspiring our work in this field.